I can hear the wailing from here: ‘But, it’s a GEORGE HARRISON song!’.

Yes, quite. I’m not here to play iconoclast – most musical legends deserve their place in the pantheon – but having said that, it’s been a long-held belief of mine that GH was the least interesting of the Beatles. Such ‘heresy’ could be discussed at length in the comments section below (that’s why we have comments sections on these things), but first allow me to explain myself more fully. Harrison composed many lovely tunes; his late fruition mainly due to his older and pushier peers keeping him at bay while they changed the course of late-20th century musical history. But by the White Album (‘Long, Long, Long’, ‘Savoy Truffle’, ‘Piggies’ etc.) it was no longer possible to ignore the fact that Harrison was maturing into more than just the man who could add a Chet Atkins solo to the hits. (On that note, he was also breaking free of the Country Gentleman’s influence as well. His work on the previoustwo albums, Revolver and Sgt. Pepper showing what a raw and impressive a guitarist he was turning into). And ‘Something’ may be the finest song on Abbey Road. No mean feat…

(Unfortunately, I really find ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’ to be a total bore these days. Its sequencing after ‘The Continuing Adventures of Bungalow Bill’, heralded by John’s ‘Ey Up!’ remains for me the only thing that holds the attention. It goes on far too long and is particularly ‘whine-y’ to my ears. And let’s not get started on Clapton’s contribution…)

Enough digression: we’re here to look at a song which preceded this flowering. An out-take, recorded following the sessions for Sgt Pepper, IATM (as I shall henceforth refer to it) was finally used as a contract-filler for the 1969 animated feature: Yellow Submarine. Its place at the climax of the film luxuriates in some heady visuals that (like the song) attempt to convey some small part of what the LSD experience entails. Its lyrical surrender to the infinite sounds (to younger ears) like a wonderful abdication of reason and responsibility to the awe-inspiring lysergic revelations that Leary et al proclaimed.

Mainly restricted to a G major pedal point, its drone-like vibe approximates an ‘exotic’ raga while throwing in a series of cute lyrics that ape his more proficient songwriting pals’ mysticism-meets-suburbia brand of English psychedelia that they’d perfected on Pepper (‘Show me that I’m everywhere, but get me home for tea’ etc.). It’s a song that’s heavy on effect and light on real substance: failing, under close scrutiny to really be more than a basic modulation between G and C major. What really only appeals in the original after a few listens is the startling introduction that uses snatches of backward vocals, feedback (described by Ian MacDonald in the ever-essential Revolution in The Head as ‘ham-fisted’) and the somewhat post-modern feeling produced by Harrison, who starts to sing the Mersey’s 1966 hit, ‘Sorrow’ during the outro. George Martin’s (later) addition of trumpets pissed off Harrison, but that just shows you that he didn’t have the maturity to fully realise that the song was a dud that needed tarting up with some tried and tested cod-baroque nonsense (in this case a snippet from Jeremiah Clarke’s ‘Prince Of Denmark March’). Ian MacDonald is typically unswerving in his dismissal of the song, calling it a: ”protracted exercise in G-pedal monotony”

But speaking of ‘tarting up’ (which is what this blog is mostly about), let’s look at the version that’s featured here: Steve Hillage‘s.

Hillage is a bona fide, 100%, grade-A hero of mine. Since I was a teenager who heard Gong, I’ve loved his fluid, eastern-tinged and, yes, mystical playing. Less so his lyrics, but that’s also key to unlocking the splendour of IATM. I’d argue that it was songs like Harrison’s as well as the pyrotechnics of Hendrix and the Canterbury peers such as Caravan and Soft Machine which set young Steve off on his odyssey through what can only be described as ‘new age rock’. The combination of spiritual vaguery and killer playing were what marked most of Hillage’s output, combined with genuinely exploratory work in electronics and what would come to be known as ‘world music’.

I could easily write a whole book about how his style has been an inspiration to me over the years. Not necessarily in my overall approach, but certainly in terms of innovative techniques and the philosophy behind playing. Eivind Aarset holds the same sort of place in my head, both men represent what can happen when guitarists, scholled in the rock idiom can think beyond the norm. But, without going into too much detail, just about anything he recorded between 1973 and 1979 (the first three years covering his work with Gong among others) is worth checking out. Apart from the consistent application of the modal merged with the pentatonic in a multitude of space rock solos that pepper these albums, you also get a ridiculously wide range of exploratory genre work incorporating jazz; Canterbury (esp. Fish Rising 1975); P-funk (Green and later); electronica (he worked closely with Malcolm Cecil, the man behind T.O.N.T.O.’s Expanding Head Band and Stevie Wonder’s early ’70s synth explorations) ambient (1979’s groundbreaking meditational piece, Rainbow Dome Rising); world music (particularly middle eastern modes and instrumentation cf: ‘The Glorious Om Riff’ from Green or ‘Earthrise’ from Open) and new age philosophy, including UFOs, aetheric plant spirits, astrology and leylines. All of which points directly to his post rock emergence as a purveyor of EDM (with his partner, Miquette Giraudy, in System 7).

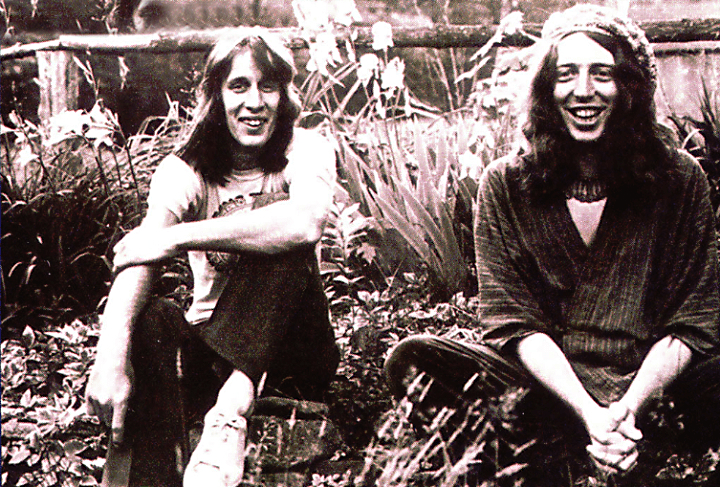

Following his solo debut in 1975: Fish Rising – mostly written as a follow-up to the debut by his pre-Gong band: Khan – Hillage was of a mind to consolidate on the buzz surrounding his guitar wizarding status in the press and amongst aficionados. Enter one brother spirit to act as producer: the comparably spiritually restless and musically inquiring Todd Rundgren. In many ways Rundgren is the absolute American equivalent of Hillage. His lyrical concerns by the mid-70s were every equal to Hillage’s evocations of post-hippy esoteric (or, to be more accurate: MAGICK) values. And he had also combined these musings with knotty progressive work-outs interspersed with his own variation on guitar mastery (truth be told, when he formed his parallel band project, Utopia, in 1973, he was completely in thrall to english prog by the likes of Yes). But in the end, Rundgren is the ultimate musical dilettante and his body of work covers a far wider (and far more American) stylistic base than Hillage. Oddly my love of TR started at the point where I realised that he was attempting to elevate the pop song to a higher level. It was only later that I grew to know and accept his more mystical side. Perhaps it was his innate (and legendarily) ironic tone that made him less believable on such matters. Hillage, somehow – possibly from his time spent working with that eternally mischievous pixie, Daevid Allen – never lost his ability to convey an almost childlike wonder at the mysteries.

The resulting album (on which can be found Steve’s rendition of IATM, as well as another incredibly telling cover of a slice of prime english psychedelic whimsy: Donovan’s ‘Hurdy Gurdy Man’) was L (1976) and in most ways was a success, although maybe not quite the match made in heaven that it looked on paper. I’ll freely admit that in my youth I found Todd’s production style clashed with Steve’s sound. Without a backing band at that point, it fell to Rundgren’s Utopia to fill the role. Todd’s boxy drum sound and more compressed production style seemed at odds with the message within.

But despite this, it’s obvious that Todd was mostly sympathetic to this eccentric english guy and his french partner in their quest to prolong a ‘second psychedelic wave’ as Hillage explained it to Rundgren when they met. Moving away from the knottier Canterbury/jazz rock sound of his previous album, this was a stab at a more focused, crowd-pleasing blend of space rock guitar, progressive over-ambition (‘Lunar Musick Suite’: note the ‘k’) and singalong sensibility (the aforementioned cover versions as well as his own cosmic country tune, ‘Electrick Gypsies’ (again, note the ‘k’), and, naturally, new age baggage. Many of Hillage’s most enduring stage numbers spring from this album and it proved to be the absolutely right move to gain the only kind of widespread acceptance that this kind of stuff could reasonably expect in the UK in the late ’70s. Growing up in the West Midlands at this time probably made it seem even more alluring. Who knows?

But, ending the album as a triumphal coda to the 12-minute ‘Lunar Musick Suite’ (complete with pocket trumpet solo by Don Cherry) comes, perhaps, Steve’s defining moment as a guitarist. One lousy song…

Hillage’s version stays fairly faithful to the original – opening with a big G major that bleeds into (distinctly not hamfisted) feedback and up pops the ‘caliope’ (as Rundgren describes the farfisa-through-a-leslie-speaker sound he was trying to reproduce from the original). At the 0’25” mark the first difference occurs: Todd had recently relocated his Utopia Sound Studio to bucolic Woodstock and was, in effect, testing out all his (and Utopia’s) new gear. His pre-release Eventide Harmonizer gives Willie Wilcox’s drums a sound like a sledgehammer when they rumble into view. From hereon in, it’s the same old nonsense about floating down the stream of time and the love that’s shining all around you blah… It IS kind of monotonous.

At the 2’13” mark a standard Hillage mini solo arrives but only serves as a filler before Roger Powell’s keyboards enter, taking the part of the baroque trumpet (at 3′ 39” he duplicates the ‘Prince Of Denmark March’ exactly as in the Beatles’ original). Up until 4’30” the listener seems set for the same warbling, directionless conclusion as Harrison’s and then… BAM! Everything stops for Steve’s real solo. Starting with a whammy bar move that’s atypical for him (even though by this point he was using his mid-60s Strat for most work) he divebombs into a solo that contains everything I’ve talked about up until now. Flurries of modal runs with an eastern flavour that climb the fretboard and finally unleash themselves in a delay drenched wah-fest. Hillage’s armoury of effects and tricks was, by his point, completely up to par: signature moves involved the use of quarter note delay (with an Echoplex in those pre-digital days) to produce spiralling arpeggios; fuzz-drenched tones; and the further development of ‘glissando’ technique (learned from former boss, Daevid Allen, utilising strings stroked with polished steel implements), but here it’s his mastery of the aforemention wah pedal that is astonishing. His tonal control adds an ocean of extra expression as he modulates – making the sound soar majestically in a way that George Harrison would never have been able to accomplish.

However, the reason I include this lousy song is not because it contains Hillage’s finest guitar work. Far from it. His canon is carpeted with wonderful enveloping, elegant, playful examples of why he’s a true innovator. One reason for its inclusion is that it demonstrates another aspect of Hillage’s playing that’s less acknowledged: his ability to insert an apt and concise solo when working within a poppier framework. He does it again on another cover version (this time it’s not a lousy song): Buddy Holly’s ‘Not Fade Away’ from Motivation Radio (1977). On the album version he cheekily inverts convention by beginning with the solo. It’s a corker, too.

His work with Gong (esp. Angel’s Egg), Kevin Ayers (Bananamour’s Shouting In A Bucket Blues’), Egg and many others all bears the same stamp. Even when he’s at his furthest out, he still has a strong pop funk connection that really kicked in on the aforementioned Motivation Radio just got stronger with each release.

And, of course, I include the song because, once more, it demonstrates the power of a decent solo to elevate the banal, the dull and the plain hopeless to another level. In this case, it’s quite literally an astral one. And, in the parlance of my forebears, it really is too much…